Chronicles of Exile: Letters from Chevengur,

An Illustrated Journey Through Platonov's Communism

by

Tora Lane locates a problem of modernity as a “fear of finitude”; she writes, “Modernity...thinks of continuity as the replacement of one time by another, and will therefore constantly chase its linear projection and be blind to the incongruities of the time” (Lane 56). Modern society relies on an illusion of progress, of momentous events leading society forward and upward along a cohesive, coherent trajectory. This is one of many illusions that disintegrated plainly in front of my eyes when the global pandemic broke out and I was confined with my parents in the house I grew up in. In a matter of days, the country shut down, and cracks began appearing in this continuous upward trajectory, on a global scale and in my daily experience of time. After two weeks in confinement, my journal shifted, from to-do lists, check marks, proof of daily existence, to an inward roaming of sorts, one marked by subscendence rather than directed momentum.

April 3rd: The days are blurring together... I can barely remember what day of the week it is. It’s difficult to focus when news of the pandemic is crushing, and work feels meaningless when I’m alone. There is an excess of time.

Moving forward sometimes feels like you’re going backward. It doesn’t feel good. Especially right now. I am in a state of heightened agitation...

...Time has become irrelevant; in fact it has almost completely dissolved. Existence is a continuation of activities that are put down and resumed as the sun rises and sets. Now, maybe we can all stop pretending we have anything figured out or decided upon.

I also began having troubling and vivid dreams that would seep into my waking life:

I must’ve only slept for an hour, maybe two. I dreamt of an old VHS movie, the credits rolling, on a street somewhere in New England. I leaned forward and fell into the scene, and I was suddenly standing there on the pavement. I looked down and saw a fork. I turned, making a sudden movement, and the fork went straight through the bottom of my foot. It hurt a bit, and when I pulled it out, people around me got wide-eyed-- “It looks pretty bad”-- I looked down, blood was pooling under my foot. I became light headed, looked away, then fell to the ground. I could feel the blood leaving my body, but no one was helping me. I awoke with a jolt, convulsing from the cold, unable to stop shivering. I felt my hands and feet; they were completely numb. I turned the light on to make sure I wasn’t actually bleeding. My foot hurt in the place of the dream wound. The rest of the night was restless. I lay shivering, covered in blankets.

My feet, which had carried me thousands of miles, were suddenly freezing up. I had been on the road for months, living nomadically and never standing still. The constant movement had come to a standstill. I could no longer escape into unknown places. In confinement, time folded in on itself. I began experiencing waves of melancholy, grief, indifference, and stillness. I began learning how to inhabit my own body again, moving through various states of self-awareness, in close proximity to my dreams, thoughts, memories, and hopes. After several weeks, I entered a state of limbo: what was to come of this boredom and longing? It was in these conditions that I began reading Chevengur, a novel by Andrei Platonov, a Soviet writer who inhabited and wrote about a different kind of limbo--the upheaval and aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution--a limbo that is perhaps adjacent to our own precarious position. When a sudden crisis knocks the ground out from under us, and we are unable to return to the way things were, how do we move forward? How do we inhabit ourselves, our minds, our bodies, our world?

The week of George Floyd’s murder, I lay awake at night, restless. I began sleeping at 9:30pm, waking at 1am, unable to fall back asleep until the sun rose. In the dark of the night, when everyone else was sleeping, I read Platonov. His world was an escape that brought me back to reality. In these hours, between bouts of dreaming, I felt I was inhabiting an alternate dimension--somewhere between yesterday and tomorrow, in between the despair of the present moment and the hope of a better world.

As I wandered through Chevengur by night, I found myself at a loss for what to do during the day. Everything that once felt productive and useful suddenly felt unnecessary. From this new, empty, open space emerged a compulsion to create. What came out of this was a series of paintings, my own iterations of Platonov’s unique vision. My attempts to realize the truths and mysteries of Chevengur through illustration marked a point in my journey through self isolation, as I grasped for meaning in the destruction and ruin of everyday life as I knew it.

Communism and Return

Platonov’s characters experience the tremors and aftermath of the 1917 revolution in Russia and embark on their own metaphysical, melancholic roamings. They are in search of an esoteric communism, one which they are unable to locate, although they are told it has already arrived. When Kopenkin finds Chevengur, the town where communism has come to fruition (so he is told), he writes to Dvanov: “Dear comrade and friend Sasha! There is communism here, and return. You should be on the spot as quick as possible.” However, the two begin to question whether this is indeed the utopia they’ve been searching for. In fact, all of the characters seem puzzled by their current situation, and no one has a clear idea how history is unfolding. Observing reality becomes a tricky and exhausting process for everyone involved: the characters are “convinced something must be done, that someone is guilty, but they have no idea what or who, and they sense they are not really at home in their cognitive faculties” (Lane 51).

As a reader, one is able to enter each character’s world but is unable to transcend and see the truth of their position from above. Sasha Dvanov, the central character of the novel, is tormented by a hollow space within him, searching the Russian steppe for something he cannot name yet. He joins the Bolshevik party, and travels from town to town, imposing order based on “revolutionary spirit”; however, he receives no answers to the questions that torment his soul. His comrade Kopenkin also feels extremely ambivalent about what they should be doing and how they should be carrying out these tasks. Kopenkin values the revolution only to the extent that it could help him avenge his comrade and one love, Rosa Luxemburg, whom he had never met. For the sake of Rosa’s memory, he wonders, is this really communism? The two revolutionaries are driven by their torment, and drift through various states of awareness, with some rare moments of insight but for the most part wildly confused. However, one gets the sense that this disoriented searching is not tragic, rather it is a grasping/reaching in the dark for some new way of inhabiting the world. Through this grasping, the dream of revolution asserts itself: the characters discover ways in which “reality speaks through its meaningless attempts to establish meaning” (Lane 36).

Zakhar, Sasha’s foster-father, a craftsman and inventor, faces his own torment. Constantly surrounded by death, he must always transfer his affects to the world of machines. “Zakhar Pavlovich was not solitary-- machines were his people, constantly arousing within him feelings, thoughts and desires” (Platonov 27). Unless he is working with tools and machines, Zakhar’s grief drilled inwards, and “in his heart arose a saddened freight” (Platonov 11). Death, mortality, and the ensuing sadness for him creates an awareness of time. At first, Zakhar imagines time to be “a riddle that is hidden somewhere in the mechanism of an alarm clock,” as something locatable (30). Then, later on, when he encounters a young boy begging for food, he feels sympathy towards him and in that moment Zakhar sees “that time is the movement of woe, and as tangible a thing as any substance, though not fitting to be worked” (Platonov 32). For Platonov, grief cannot be “fixed” like a broken alarm clock, or resolved once and for all-- it can only be shared and responded to through collective representation (Flatley). Avoiding time, and therefore avoiding grief, can only lead to further death and destruction: Chepurny, impatient to “end time”, murders scores of peasants in the Russian steppe in order to liquidate the kulak class and realize the utopia of communism, while Sasha’s father, the fisherman, is desperate to possess the secret of death, and drowns himself in the hope of satiating his curiosity. Both of these characters are unable to endure time and grief, and take extreme measures to cut short time itself.

The ability to endure time, as the movement of grief, was something I began to come to terms with over my weeks in confinement. In the midst of a global pandemic, living with a constant awareness of death on a daily basis, I found this to be unavoidable. This, coupled with images of the murders by police, left me searching through the melancholy like one of Platonov’s characters. How, as a society, are we to deal with the immense grief of the present moment? How are we to face death, and our “fear of finitude”? My first response to this materialized through illustration.

Chepurny

Chepurny

Dreams

In the distance a horse stood motionless in the rolling fog of the exhaling earth. Its legs were too short for Kopenkin to be able to believe that the horse was alive and real, while some tiny person clung feebly to its neck...The sleeping man breathed unevenly and chortled joyously in the depths of his throat. He was probably participating in happy dreams at that moment. Kopenkin looked the man over completely and failed to sense in him any enemy...even in sleep his face was ready for revolutionary deeds and the tenderness of worldwide cohabitation. (155)

Surrounded by drifting fog, unable to see clearly, something speaks to us from a distant place inside our dreams. This first image depicts a sleeping Chepurny, resting upon his grazing horse. This is an attempt to capture a different kind of consciousness, one that comes from within the body and not from the rationalizing mind. Any insight as to the reality of the revolution is felt and directed not from the ideologies and slogans propagated by the Bolshevik party, but from within some unknown place of yearning inside the soul of each character.

“For some reason people always dream during war and revolution,” Zheev said. “But during peacetime, no. Everybody sleeps like little stumps.”

Chepurny himself always dreamed and thus did not know where dreams come from and why they disturbed his mind… “I’ve heard how when a bird is moulting it sings in its sleep,” Chepurny remembered. “It’ll have its head under its wing, nothing but fluff all around, nothing that you can see, and then this peaceable little voice will come out.” (Platonov 222)

With the “fluff” of party slogans being shouted at them from above, disoriented and unable to see the truth of their reality, each character fails to acquire a revolutionary consciousness. However, in the midst of this fog and confusion, during a time of great upheaval, they are disturbed by their dreams. It is this “peaceable little voice” from within that gives the characters hope that the world can be different, and they grapple with this voice in their own unique ways. One day Kopenkin encounters a “truly proletarian bird”:

Kopenkin smiled at the sparrow who had in his own fruitless crummy life been able to find enormous promise. It was clear in the mornings he warmed himself not with seeds but with a dream no man could know. Kopenkin too lived not on bread or well-being, but rather on an unreasoning hope. (Platonov 133)

Although it is usually some form of melancholia which fuels each character’s search for meaning, this “unreasoning hope” of their utopias dwells in the unconscious, as dreams that surface and are forgotten. The utopia promised from the 1917 revolution, too, lives on inside them as a forgotten dream (Lane). Dvanov, an orphan and agent of the revolution, senses that this utopia he has been searching for exists not in its realization, but rather in the inner worlds of other characters, and he is obsessed with watching others as they sleep:

Gopner was already asleep, but his breathing was so weak and pitiful when he was asleep that Dvanov went over to him in fear that life in the man had somehow ceased. Dvanov replaced Gopner’s wide-flung hand on his chest and listened anew to the complex and tender life of a sleeping man. It was plain how fragile, defenseless, and trusting this man was, and yet all the same there was probably someone who had beaten, tormented, deceived, and despised him. As it was he was barely alive and in sleep his breathing had all but flickered out. No one looks at sleeping people, but only they have real, beloved faces, for when awake the face of a man is disfigured by memory, feeling, and need (Platonov 192).

Platonov writes, “no one looks at sleeping people,” but of course, Dvanov is constantly searching the faces of sleeping people. Dvanov himself is this “no one,” as he encompasses an “asubjective anonymity” (Lane, 41). The emptiness inside Dvanov, an orphan who takes the name of his foster family, makes him receptive to others and able to experience the life of all the people and things around him. This “hollow place” makes him incredibly sensitive to the needs of others.

While wandering alone through the steppe, Dvanov stops at his father’s grave:

Sasha went to the graveyard, not recognizing what he wanted to do. For the first time he thought now about himself and touched his chest. Here I am, and all around everything was foreign, unlike himself. The house in which he had lived, had loved Prokhor Abramovich, Mavra Fetisovna and Proshka, turned out not to be his house. He had been led out of it onto the cold road in the morning. In his half-childish saddened soul, undiluted by the comforting water of consciousness, was clenched a full crushing insult, which he felt up into his throat. (Platonov 18)

The Graveyard

Recognizing that he has no home and belongs nowhere, he lies down next to his father’s graves and thinks, “Here I am.” This lack of belonging is not an impediment, in fact it is what creates the conditions for experiencing collective life. It is telling that Dvanov embraces his lack of belonging in the graveyard, where he buries his walking stick, deciding he will someday come back and live there with his father. The fact that Dvanov has no sense of self means he is able to live “through” others, including the dead.

So that all might be whole

Collective Mourning

Dvanov imagines the task of communism to be one of care and redemption for the dead. He aims to harness a collective power, not through Bolshevik slogans of strength, utopias of technology, and mastery over nature, but through sensitivity towards the forgotten, oppressed, and orphaned.

Dvanov found sundry dead things like worn out shoes, wooden tar barrels, dead sparrows, and other bits and pieces. Dvanov picked up these bits, expressed his regrets at their demise and oblivion, and then returned them to their former places, so that all might be whole in Chevengur until the better day of redemption within communism. (Platonov 322)

All will be redeemed and included in communism, even these dead “bits and pieces.” Platonov helps steer us back towards the question: how do we deal with death? At the time Chevengur was written, Platonov saw firsthand the death and destruction that took place in the Russian steppe, and the immense grief that came from it. He also witnessed a utopian movement to abolish death-- notably from the work of Nikolay Fyodorov, who greatly influenced Platonov. Fyodorov’s writing emphasized how shared loss brings people together, and he fantasized about resurrecting the dead through science and technology. (161 Flatley)

Although nearly a century has passed since Chevengur was written, it is not difficult to see a trend in our current society, with its dreams of “mind-uploading”, and extending life through technology by any means necessary. It seems that we are constantly surrounded by death but, as a society, unable to deal with it in a meaningful way. In fact, one can find a direct link between the disappearance of communal mourning rituals in modern society and the obsession with meaningless images of violent death portrayed in the media, film and television (Leader 74). In the weeks following the outbreak of covid-19 in the US, I felt all too aware of this reality. Everyday of the shutdown we watched death tolls rise and were assailed by videos of protests and senseless killings by police. More than ever, I felt, we needed time to do the work of collective grieving, in order to deal with death, not ignore it.

Chevengur directly spoke to this need. Platonov harshly critiques the utopian vision to abolish death, and we can see this through Dvanov’s relationship with his father, a fisherman who sees fish not as food but as “special beings that definitely knew the secret of death” (Platonov 6) He becomes obsessed with death as “another province” in which he can escape, thinking it might be better there. He wants to “live awhile with death and return” (Platonov 6), in case it is more interesting there. One of the muzhiks tells him, “What the hell, Mitry Ivanich, nothing ventured, nothing gained. Try it, then come back and tell us” (Platonov 6). Eventually, his melancholic curiosity drives him to drown himself in the lake, leaving the young Sasha Dvanov on his own.

The Fisherman

The abandoned Sasha, however, does not make the same mistake as his father. He is quite the opposite--he clings to that which he is lacking, holding losses close to him because they are lost or will eventually be lost. He is not an escapist. Although the novel begins with the death of Sasha’s father, his relationship with his father is ongoing throughout the novel. If anything, their relationship is renewed and restored following the fisherman’s death. Dvanov’s father repeatedly visits him in dreams, especially at crucial parts of the narrative where Dvanov’s decisions are informed by his father’s presence. In this active relationship, Dvanov never successfully mourns the death of his father. Again, we see communism as a project of redemption: Dvanov thinks, “In the future world...his fisherman father would find that for the sake of which he had voluntarily drowned himself” (Platonov 48).

Friendship

Dvanov’s inability to mourn the death of his father does not make him defective in any way-- from this place he is able to form meaningful connections with the world. Motivated by loss, he is able to develop a non-reified and non-instrumental relationship with people, animals, and everyday objects around him. That is to say, none of Sasha’s relationships are efforts to know another object. Rather, he is interested in attuning to different objects in order to share affective states and experiences with others (176 Flatley).

Sasha could not enter into anything separately. At first he sought out some similarity to his action and only then did he act, not from his own necessity, but from sympathy toward something or someone.

“I am like him,” Sasha often said to himself. When he looked at the ancient fence he often thought in an intimate voice, “It stands for itself,” and then he too went to stand someplace without the slightest need. (Platonov 53)

Sasha cultivates friendship with all things by creating similarities rather than finding similarities. Sasha’s mimetic talents allow him to exert agency over his moods, giving him a new way of engaging with the world around him (176 Flatley).

Kopenkin & Dvanov

This way of inhabiting the world allows radical friendships to open up, and these relations are not reducible to any existing frameworks for interacting. Emotional ties between characters remain situations where affects come from a shared space rather than from the core of each individual. Kopenkin and Dvanov’s relationship, for instance, is highly ambiguous--it could be read as a romantic entanglement, but Platonov’s non-judgemental, indifferent gaze prevents us from reading into their longing for each other. We observe their actions, feelings, and inner monologues, but any conclusions we bring to the text are our own. (182 Flatley)

The novel is primarily about this kind of open friendship. All of the characters are afflicted with intense melancholy, a melancholy which is specific to the social and political upheaval they are experiencing. Melancholy flows out of them as torment, longing, boredom, restlessness or even spiritual anguish, and in friendship, they find a shared place to transform it. My painting of Dvanov and Kopenkin embodies these moments of shared melancholy, as they sit under the stars, shining “from that quiet system in which the stars moved as comrades, not so close together that they would flow into one and lose their differences and mutual futile attractions.” Like the stars, Kopenkin and Dvanov will never “flow into one,” instead they send out melancholy affects that meet in a shared space, making them available for reflection and contemplation (159 Flatley). Kopenkin reflects on his friendship with Dvanov: “he had been riding beside Sasha Dvanov and when he felt melancholy, so did Dvanov, and their melancholy had rushed towards one another, met head on, and stopped each other dead in their tracks. In Chevengur though, Kopenkin had no comrade to come towards his melancholy and stop it, so Kopenkin’s sadness continued out into the steppe, into the emptiness of the black air, finally halting in the world” (Platonov 249)

In opening new relations, Platonov offers hope for a new world. Platonov’s communism is a project of collective friendship that extends not only to humans but also to nonhumans and to the dead. Kopenkin’s relationship with the deceased Rosa Luxemburg is one example of this. For him, Rosa is the embodiment of communism. Just as Dvanov hopes to make sense of his father’s death in communism, so too Kopenkin attempts to redeem Rosa’s death, and even dreams of resurrecting her in the future. Communism, then, is not about Lennin or Marx or Bolshevik power, it lies within each individual and their relationship to the dead, which they carry with them. For Kopenkin, Rosa is a tangible force in his life, leading him and his horse ahead and into the unknown.

Rosa

Zakhar

Yakov

Yakov

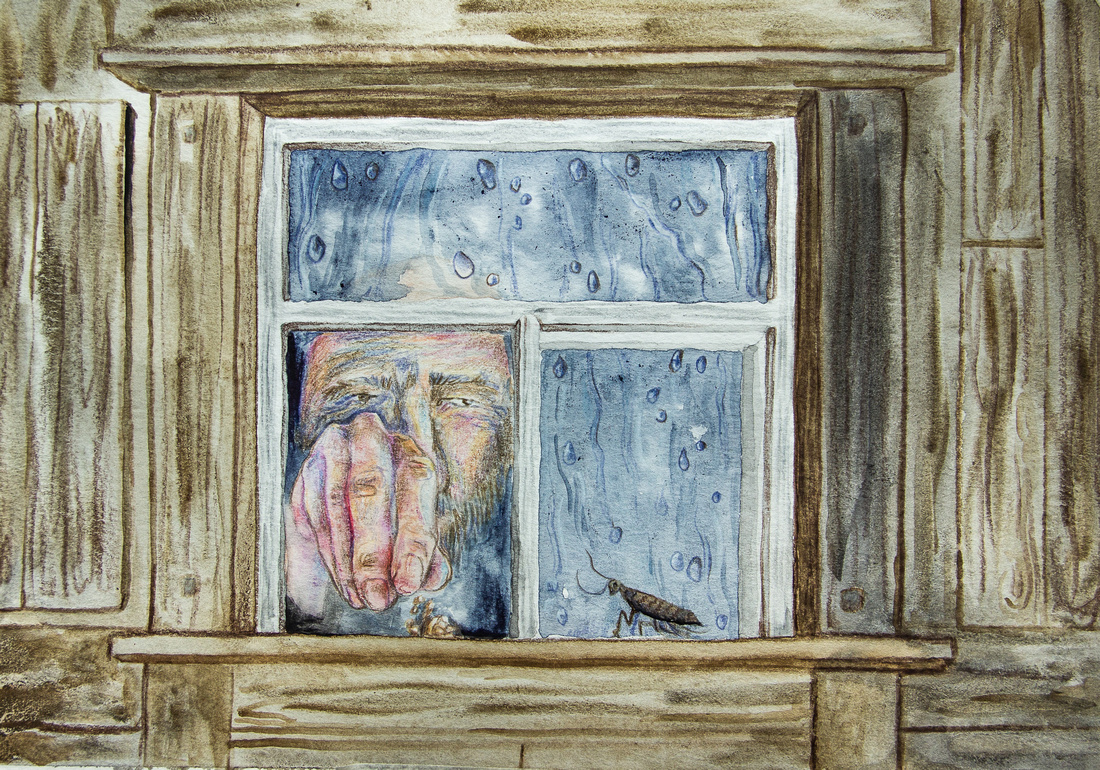

Another inhabitant of Chevengur, Yakov Titych, befriends a cockroach. “The cockroach lived obscurely and without hopes, but also patiently and stubbornly, not displaying its torments outside itself. Because of this Yakov Titych treated him carefully, in secret identifying with it.” (Platonov 271) Yakov feeds the cockroach, while the cockroach sits patiently on his windowsill. “Every morning the cockroach climbed up to the windowpane and looked out at the illuminated warm field, his whiskers trembling with excitement and loneliness” (274). When Yakov becomes ill and begins to die, the Chevengurians gather around, trying to decide how to help the sick man. Chepurny notices Yakov’s strange attachment to the cockroach and is not sure what to make of it:

“Yakov Titych, you shouldn't have fallen in love with that cockroach,” said Chepurny. “That’s how come you got sick... The entire microbe filth has flung itself at you, and otherwise it would have attacked everybody and you'd only have got a little bit.”

“Why can't he love a cockroach, comrade Chepurny?” Dvanov asked uncertainly. “Maybe he can. Maybe the fellow who doesn't want to have a cockroach will never want a comrade for himself either.”

Chepurny immediately fell deeply thoughtful, during which it seemed as though all his senses stopped, so that he understood everything even less.

“In that case, then please, he can get attached to a cockroach...his cockroach can live as he likes in Chevengur, too.” Chepurny concluded with that consolation. (Platonov 278)

Here we find yet another example of Platonov’s insistence on making space for unusual and ambiguous relations. In his communism, all will be included, even the cockroaches. Love and care are not constrained to normative formulas; nothing is excluded in advance. This image of Yakov also captures a feeling of confinement, of reaching towards other beings from within the darkness.

This act of reaching is where I began and ended my journey through Chevengur. The novel, which opened a space of friendship and solidarity, concluded with the death of almost all the central characters, leaving me feeling a great sense of loss. However, along with this loss, it left me with a feeling of hope, pushing me away from the pages of the book and out into the world. The loss I felt was not tragic or depressing, it was a loss motivating me to create communism in acts of friendship everywhere around me. Although physically confined to my childhood home, my ennui and melancholy, which I had previously felt turning in on itself, now had somewhere to go--out in the endless expanse of the world there was immense possibility. Like Dvanov with his mimetic talents, I felt compelled to live life collectively, to endure the grief of time with others, and to constantly reach for new modes of relating.

Bibliography

Flatley, Jonathan. Affective Mapping: Melancholia and the Politics of Modernism. Harvard College, 2008.

Lane, Tora. The Forgotten Dream of the Revolution. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2018.

Leader, Darian. The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia and Depression. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2008.

Platonov, Andrei. Chevengur. Translated by Anthony Olcott. Ann Arbor: Ardis Publishers, 1978.