Meaningful Silence: From Isolation to Reform,

A Little Essay and Some Photos

by

Artist’s Statement:

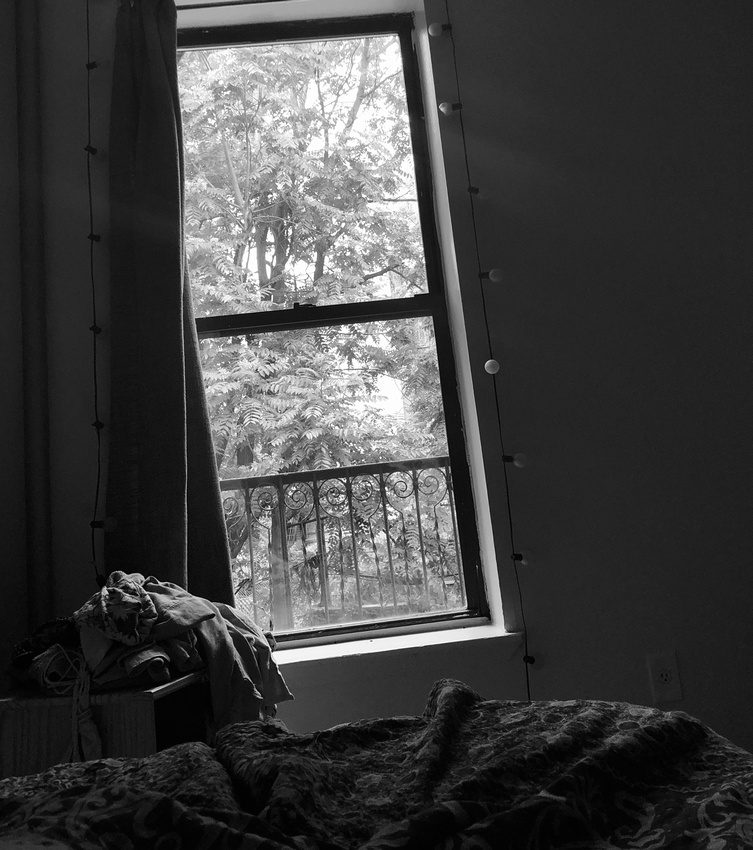

This work is a reflection of the times spent during quarantine, doing research, thinking about nothing and everything concurrently and attempting to find words to match this indescribable moment. I wanted to write something in the creative nonfiction format, that fused a personal, memoir or chronicle-style prose with research and analytic reflection. I began somehow by obsessing with the idea of MTV in the late 80s/early 90s, and thinking about how the heyday of MTV felt diametrically opposed to whatever it was I was experiencing in quarantine. MTV felt so carefree, so loud, so crowded, as opposed to an isolation spent constantly perplexed and carefully fixated on unending critical and existential questions. Just as MTV seemed to be some kind of reflection of that era, I felt like the protests and social unrest that spiraled into Summer 2020 was a small reflection of the era of the quarantine. This essay tries to connect seemingly disparate topics- the topic of “spring break” and the fight for racial justice in America- through the meaning of quiet and stillness that existed in my quarantine during the first height of the COVID-19 pandemic in NYC. The photos that accompany are photos of isolation and photos of the beyond: the protests. They are meant to serve as a supplement to the essay. I tried to capture in the photos taken about isolation the spirit of quiet and stillness of being stuck inside one’s own living space, and then I tried to capture the liveliness of solidarity that I witnessed every day in protests in Brooklyn.

“This quiet, all it hath a mind to do, doth”

-Robert Browning

March, 1986. Millions of high school and college students sprawled on a sectional couch at their parents’ houses, or sitting cross-legged on the dingy carpet in a dorm building’s common room parked in front of a communal TV, become suddenly propelled into a frenzy of experience unfolding on the screen. It was unlike anything they had seen before. Perhaps they are watching passively, treating the television’s volume as background noise, or perhaps it will alter their understanding of entertainment for years to come, but assuredly, it is something nearly impossible to ignore. It’s spring break for students statewide, and while some students head out of town to holiday, the majority of young people are taking advantage of spring break for the eponymous purpose, to embrace the spirit of rest, to fall face-deep in their pillows and take a break. Often it seems spring break was an opportunity for students to remove themselves from the framework of school, which, at that age, is typically synonymous with a social life. Spring break could be read as an unconscious subscription into the philosophy of “checking out,” of embracing leisure, rest, and embracing the quiet. But, in 1986, MTV rewrote the meaning of spring break with their first ever “Spring Break Special,” a live-televised event showcasing spring break as a hedonistic adventure, a place for young people to abandon reservations and embrace the spirit of debauchery.

***

My recollection of a typical middle class, middle America spring break looked like a burnout’s derelict paradise. My parents left the house to work, leaving my sister and I to our own devices; translation: the days were long, hazy, lazy, surrounded by the complete silence of absolute stillness. We were too young to really go anywhere by ourselves, our only option was to pass the day in the house. I would soak my body into a green leather couch in the caliginous basement to where all the winter’s cold would travel. After wrapping myself in a heated blanket, I became the ultimate settler. The space was my dominion, and I would not move for the remainder of the day. With nobody around, and most sources of neighborhood activity and noise-traffic away at work, the house fell absolutely quiet. The silence was like a dream, and in fact, very little distinction between a dream and reality was necessary. I allowed the quiet to consume me. I felt the heat of the blanket permeate through my temples and I sometimes reveled in the movement of the sky, from one hourly indication to another. Usually, the only way to signify the passing of time was to acknowledge the height of day, when the sun reached the basement to offer a sliver of momentary daylight, peeking through the perpetually closed shades. Or, the time would become clear when I was startled into a consciousness of presence by the roaring clinks of the garage rolling open; signaling another workday realized and the bustling evening movement of my parents upstairs soon heard, like parade drummers rehearsing on an early Saturday.

The wares of adolescence made my days off from school irrevocably yet pleasantly long. My impulse towards immobility palpated the sensation of quietude. I noticed only the buzzing of the refrigerator or the wind tickling the air around me, but even still only minutely. My sister, always the ardent reader, mostly devoted the days to her paperbacks, and I, a bit less academically inclined, would watch whatever was playing on TV. I recall my keen ability to faze out the sound. The silence of those days had a texture. The air, crisp from the Colorado winter kept to itself, and the fine orange-peel walls in the basement TV room swelled with insulation, as if to assure me my comfortable silence could not be broken. I also recall, buried somewhere in the trove of my memory, an abrupt interruption of that silence. The first time I remember the quiet breaking is also the first time I remember being exposed to MTV's Spring Break Special. Routine: I would power up MTV, watch nonstop muted music videos, and let the day fade away. Once, however, the programming on MTV was too striking to mute. The cacophonous yet intriguing voices of attractive, belligerent and unconditionally confident college students pierced through my quiet. The value of silence fell slowly underneath my feet.

In many ways, MTV in general felt like the ultimate betrayal of quietude. During the dry heated summers as a kid, I would retreat back to my nook, and to my lackadaisical spring break ways, only this time to embrace the cooling dominance of the basement’s dark flare. While MTV’s Spring Break specials were a blatant haven for televised chicanery, summer vacation often showcased Total Request Live, a live-studio audience all-for-one extravaganza. The show featured softball interviews with promising young pop stars in the bud stages of their blossoming fame, phone call requests for music videos, messy competitive games, and sometimes pre-recorded content, purportedly with a “comedic tone.” Perhaps most notably for me, Christina Aguilera debuted her video “Dirrty” on TRL in the summer of 2002, signaling her transformation from “Mickey Mouse Club” alum and verified bubblegum pop “good girl,” to a fetishistic dreamboat. Her album Stripped, and the Dirrty video signaled Christina Aguilera’s consent to a new interpretation of her body as, not only adult and mature, but sexualized, stripped, and loving it. The “Dirrty” video is an exhibition. Aguilera arrives at the video’s setting in a cage that, once opened, seems to exalt her affirmation of abandonment, squirming away her cookie-cutter image. As she dances in a locker room shower, or a grimey boxing ring, her lyrics “want to get dirty/ gonna get a little unruly” echo her intent to dissolve notions of appropriateness, calling out to her competitors “give me some room/I’m coming through/ I’m overdue/It’s about time.” In a 2018 interview with Aguilera, reporter Jason Lipshutz asked if she regretted the video after receiving vociferous backlash against her new intentionally-sullied image. Her answer to the question claimed she did not intend for the song, or the album Stripped, to have a sexual connotation at all, but rather it was “about being 21 and coming of age.” Still, she contends, Dirrty is her favorite video because it represented the moment in which she found her “independence,” becoming free from the instructive grasp of her music label. This duality, though, between her intention and the hypersexualized reaction to her work begs me to wonder about whether twenty-one year old Christina Aguilera actually was aware that in liberating herself from one prescriptive pop culture box, she seemed to be unknowingly consenting to enter into another trope, one that seemed more interested in simply exploiting her body than in exploiting her for an image, a symbolic representation of a certain value. Generally speaking, independence feels more like a farce than a serious destination in many sects of American culture, and the river of exploitation runs so deep, yet can be so subtle, that most people don’t even know they’re drowning.

There was something electrifying about the way MTV broke the standards of the norm, but the politics of consent on those shows seemed oftentimes incredibly grey. That spring break, my impulse to raise the volume and see what was happening on the Spring Break Special overpowered my peculiar addiction to the quiet days of the past. About a decade later, congress passed the monumental CALM act, regulating the volume of advertisements to assure commercial breaks were no longer blaringly aggressive. MTV had always been notorious for the consistent commercial breaks; five minutes for breaks for every three to five minutes of content was not at all uncommon. The noise emanating from MTV’s Spring Break Special rolling through my television not only felt louder than the silence I was used to, but the steady streams of commercials guaranteed the capture of my attention.

MTV’s Spring Break Special paved the way for a new standard of television content. When the show first aired in 1986, it conquered a completely original, raunchy and chaotic tone. Broadcasting from Daytona Beach, Florida, the often shirtless host Pauly Shore would run aimlessly through crowds of semi-naked, unbelievably attractive teens, and revel in the abundance of bodies willing to do whatever he requested. The mainstage of the “fun,” and perhaps the backbone of the entire program, rested on the outlandish contests. While comprehensively planned, the contests’ execution fell short on the degrees of professionalism. Only two things seemed to matter in the games: girls and ALOT of whipped cream. Anybody who managed to understand the rules of the games well enough to win, then became the recipient of some truly dippy prizes. Want John Mellencamp to grill at your backyard barbecue? Maybe this year, why not have the British band The Who to do your taxes? Just play a game of trivia, in which the categories are not on a Jeopardy board, but instead listed on the bodies of bikini-clad “babes!” And don’t forget the slippery and sticky catwalk graced by college kids strutting their personalized whipped-cream swimsuits, meanwhile Adam Sandler a.k.a “Studdboy” announces on the microphone, offering sage sex-advice to a trough crowd packed with teenagers: “always look both ways before pulling out.”

Like confetti, the show exploded and oozed little messes everywhere: a pure exploitation playground. It wasn’t until a few years later in 1997 that a production assistant for MTV named Joe Francis stepped on the scene, insisting further on pushing the boundaries of exploitative Spring Break content. The madness of MTV’s Spring Break show paved the way for “Girls Gone Wild,” an even more cloying and salacious display of licentious teenage behavior, perpetuated and encouraged by the ever-so mawkish Joe Francis, who, eventually went on to encourage Kim Kardashian to capitalize on the press she was receiving following the unconsentual release of her sex tape. There was something so clearly wrong, yet so curiously captivating about the MTV experience of those days. Still today, the MTV Spring Break special carries a lasting cultural weight. Despite the active “de-emphasizing” of the program after 2005 by MTV executives, the morale of the program continues to leave an impression on affectable, particularly White, Americans- who are still willing to uphold the spirit of spring break at any cost.

*

I have not had unmitigated quiet time since those early childhood spring breaks. For many years, spring and summer vacation meant a time to bask in solitude and sluggishness. As I got older, though, the vacation time quickly transitioned into a time to work. I cycled around town, visiting disheveled suburban homes of overwhelmed moms- desperate to cut me a check for keeping an eye on the kids while they snuck away for an afternoon nap. Without the safety net of children keeping away at school for the majority of the day, the lives of suburban mothers quickly tangled, thus the need for thirteen year old me to the rescue. Like it did for the overworked moms filling my pockets with petty change, having a spring break away from school did not represent leisure. I started to bank a new routine for the imposed breaks, especially as the rigor of my academic journey heartened. I eventually graduated into using the time to get more work done, to catch up where I was behind in school, or to pick up extra shifts for another buck. It was a work ethic that seemed to spare no time again for the frivolity of dormancy, of embracing quietude.

By March 2020, the lethargy of my former spring breaks recoiled as a distant memory. I was working the most demanding job I’d ever had on a film set with a notoriously garrulous creative team: an indecisive director and a legendary cinematographer who spared no care for the sanctity of the crew’s personal time. The days typically spanned beyond the expected twelve hours, reaching into consistent fifteen, sixteen hour shifts with little turnaround for the following day. Exhaustion was a state I had little time to acknowledge. Mid-March: I arrive to set early, earlier than usual, to greet two hundred background extras pouring in for their big day in the spotlight. The day marked a significant turning point in the production; once this day finished, the project would soon wrap as well. I sported my winter parka that day, but spring was around the corner, and so too, was the novel strain of the Coronavirus, COVID-19. The air felt wintery but it was spring, and COVID-19 would begin rapidly spreading from China to Korea, Italy, ultimately to the United States and to the rest of the world. I barely registered the early reports; hounds of people stampeding the grocery stores in European countries, China already in lockdown, Italy as we know it, crumbling under its legendary feet. I was too busy shuffling in and out of an ice-box film stage at all hours of the day to really give much notice to the reports of the virus moving around globally. What surprises me is how cavalier I seemed to be at the time. So concerned with the flux of never-ending daily tasks left me mostly separated from the inevitability of a historic culture halt. That day, I arrived to work early, only to be sent home. “Crew safety,” I was told, by the studio guard who knew probably as much as I did about what was going to happen to us, our jobs, the production, New York, our families.

By the first week of April, the evening news flashed constant footage of people in China and Korea conducting mass tests, shutting down their streets, wearing white surgical masks to collect groceries. The novel Coronavirus officially reached pandemic status. And despite the best efforts of many government officials to deny, the pandemic was seeping into the vulnerable pores of American cities. Catholic priests were squirting communion wine out of a toy gun to drive-by patrons in their cars, airlines were shutting down most of their flights, and Broadway had officially closed down. I was, for the first time since grade school, stuck at home. The tornado of chaos in the grocery stores, on the streets, on the news was as loud as ever, and suddenly, there was nothing. We were told to quarantine, to stay at home; and it seemed the majority of New Yorkers, including myself, stuck to what we were told.

Memory: two days before being sent home to shelter-in-place, I was on the subway train heading to work, with my noise cancelling headphones on; no music or podcast playing, simply attempting to capture a momentary bud of silence before a busy day, when a woman began screaming. Uncontrollably, at full volume, seven in the morning, this woman belted incomprehensible drivel. In that moment, she reminded everyone on that overcrowded, standing-room-only train car, that to revel in quiet is nearly a fantasy for anyone in New York City. When I took the train that following Monday to pick up something from the set before properly quarantining, the train was completely empty. It felt darker and slower than before. In the abandoned underground, it felt like the city had never existed. Suddenly, my days were spent flooded in silence, in stillness. Like Samuel Beckett’s titular “l'Innommable,” who declared “can it be, that one day, off it goes on, that one day, I simply stayed in,” I woke up one day, and simply stayed in. I didn’t so much as pick up my feet to trundle between my bed and my couch. I stayed in, and even more, I stayed put. In those early days of quarantine, I teleported to my parents’ basement, ten years old, slothing on the couch and listening to the silence of the walls. Because New York’s count of COVID cases rose exponentially in only a few short weeks, the stay-at-home became law. The city shut down completely except for essential workers. The streets were bare. For a while, even the great dunes of sidewalk trash bags and curbside broken appliances that always decorate our beloved New York spaces seemed to disappear, even the inanimate decided to stay inside.

Gogol once said “the longer and more carefully we look at a funny story, the sadder it becomes,” evoking an old adage that goes something like “if it weren’t so sad, it would be funny.” I often associate coincidences as perhaps the universe having good humour, something considerably funny. It’s funny to me, only because I can’t seem to find another, more apt word than “funny,” that my quarantine-induced “spring break” quiet broke suddenly in the same way it had many years before. As I was sprawled sleepily on my bed in quarantine, I flipped on television to see images reminiscent of the insane horrors of MTV’s Spring Break, except now, the party coverage was a headlining story on the nightly news. This time, the imagery of spring break partying secreted a darker tone than ever it did before. This time, spring break partying had dire consequences. This time, spring break meant probably, people were going to die as a result of the activity in the footage. I sat up on my bed, that also doubled as a couch during lockdown, cocked my head right and paid attention.

The evening news paraded videos and images of young people seemingly protesting their right to party. Through these images, it became clear to me that certain Americans seem unable to remain quiet, to be still, or to respect the public health of others. They must always be moving, to create loud chaos. To sit by the pool, or the beach, or to flood lakeside hot tubs in the Ozarks with new COVID cases. It doesn’t matter the risk, these camps of Americans insist on being seen and heard. And in many cases, it is only through trivial, drunken rowdiness that they can receive such attention. In the end of March, towards early April, the governor of Florida forced all beaches to shut down after a stream of COVID cases infected students, fresh off of debaucherously uncontrolled spring break festivities. One after another, the Global News Network featured interviews with teens/twenty-somethings defending their right to party. One teen said about the importance of breaking quarantine “I just really didn’t want coronavirus to be messing up my spring break.” Another girl, pointing out that she had just turned twenty-one that year, stated that she was in Florida to party and “get drunk before everything closes.” One kid in Clearwater Florida, hiding a horrible buzz-cut head under an obscenely labeled trucker hat and a sunburned face declared “if I get Corona, I get Corona. At the end of the day, I’m not going to let it stop me from partying.”

It was impossible not to notice in the video footage of mid-pandemic Spring Breakers, the overwhelming Whiteness of the crowds. The people who simply decided the pandemic was not something worth considering with an air of seriousness, are also the people with the privilege to spark problems out of trivial nothingness. The Americans who seem incapable of resting, of embracing the quiet, are the Americans who weren’t directly impacted by Coronavirus on a plaguing level. The most vulnerable people; the undocumented, the poor and communities with greater densities of people of color in America witnessed Coronavirus take over their lives like a rapid breath a swimmer takes when finally bulging their head above water; one moment the swimmer is rolling through the waves, and suddenly, with no breath in their lungs, the immediacy to breathe becomes piercing and inescapable. Spring Break this year was not just a carousel display of binge-drinking and lechery, it was an exhibition of privilege. The people working throughout the pandemic, or the people of color sheltered-in-place to avoid contracting a virus that disproportionately affects them, or to avoid a hospital trip in a potentially racist hospital that may cost them their lives, didn’t have the privilege to consider the Coronavirus something that was simply “messing with spring break”. In many ways, though, one can watch MTV’s Spring Break Special and notice that spring break has always been a blaring example of white privilege.

In Harmony Korine’s 2012 drama Spring Breakers, a group of four young (white) girls wax poetic about the monotony of their days on a small college campus. The primary concern for these four friends is escaping the boredom of student life, and desperately wishing to “experience something.” The girls are restless, because they can be. They are not tired, they are privileged enough to be bored and they want to be a part of something “real.” As the plot unfolds, the certain “real,” or transformative experience they reference becomes inextricably linked with violence. In order to raise the money to go on Spring Break in St. Petersburg, Florida, the girls hatch a plan to rob a local business at gunpoint. They spray paint fake guns, cover their faces with balaclavas, and storm into a local restaurant, looting money from the purses of patrons and cleaning out the cash register. What seems important to notice, is the fact that the business where the robbery takes place, is a Black-owned business, and everyone sitting in the restaurant are Black; forced at gunpoint to give up their money. Then, in the final act of the film, two of the girls still on spring break use actual guns to massacre the home of a local drug dealer. Not coincidentally, the victims of the violence perpetrated by the “spring breakers,” are all Black. A montage earlier in the film shows clips of the empty hallways and the quiet campus, then cuts to an interior classroom, where we see those two girls consumed with ennui in a packed lecture hall. The girls write notes to each other, joking around about sex and boredom and one goes so far as to shoot off a finger gun against her head, indicating, evidently, that she is so bored she would rather die. That lecture, the one that is suicide-inducingly “boring,” is a lecture about Jim Crow. The subtle racial tensions in Spring Breakers seem to represent Harmony Korine’s poignant commentary about the problematic hedonism of spring break as a phenomena. On spring break, the girls have an experience they describe as “transformative”, one that feels like a dream. They are living out some sort of American Dream, on this break, but the reality of that dream is a myth. In order to achieve that experience, the girls had to ignore very significant racial elements of what was happening around them, and they had to invoke violence on both Black bodies and Black spaces to break free of the humdrum of their own lives.

Every year, the crowds of droll spring breakers leave their various beach party scenes completely trashed. It doesn’t even occur to those who aggressively party along the beach that someone else may have to pick up their mess. One of the only tales involving college students picking up after themselves following spring break was an instance recorded by the Huffington Post, involving a group of people from the historically Black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha at Florida International University, returning to South Beach after days of partying to “break the stereotype,” that spring breakers never clean up after themselves. No similar stories about predominantly white fraternities or organizations came up during my research on public messes marked by partiers. I can’t help but wonder, if this year, by ignoring the quorum of scientists asking people to stay at home, the spring break partiers can be read as intentionally inflicting direct violence (in the form of a disease) onto communities of color. Their desire to be loud, to be heard, and to be seen overpowered a confrontation with the racial dynamics of the Coronavirus pandemic. This type of ignorance is, of course, a privileged ignorance.

So there I was, like most of my fellow New Yorkers, sitting at home in silence, watching white, middle America wreak havoc on the state of the pandemic. Several news stories broke about white Americans complaining about trite concerns, probably sparked by a quarantine-induced restlessness. After the spring break stories, we saw the protesters gathering outside hospitals and outside public buildings, demanding their “right to a haircut,” and later, huge tantrums by adults not willing to wear a face covering for safety. Meanwhile, many Black Americans were entering a new level of exhaustion. So many Black communities and families decimated by the virus, mostly minority essential workers putting their health on the line to continue working, and the restless white Americans had the audacity to cry out against boredom. I think exhaustion, rather than boredom, is a better way to describe a perpetual state of Black people in America. Washington Post contributor DeNeen L. Brown rehashed a common thread in the current discourse about race “explaining racism is exhausting,” and went further to say “racism is exhausting.” Having to constantly put up with and deal with the forces of white hegemonic power is exhausting. Alice Walker describes the features of many Black characters in her novel The Temple of my Familiar by emphasizing their “tired” faces. One of the protagonists’ dad, who works for racist white landowners, is defined as a “tired, brown skinned man.” That character later can’t help but notice too, “how tired her skin was” when taking a deep look at her mother’s face. For Alice Walker, exhaustion is written into the framework of Black existence, an exhaustion that runs so deep it comes across even in the smiles of the most lively people.

The girls in Spring Breakers, or the “anti-quarantine” protesters in America must conjure reasons to riot about the monotony of their lives, because their everyday realities do not incorporate a threat of danger. If the looming presence of racism and violence was affecting their daily lives, I think the “anti-quarantine,” “we deserve haircuts” protesters would have embraced the stay-at-home order in a completely different way.

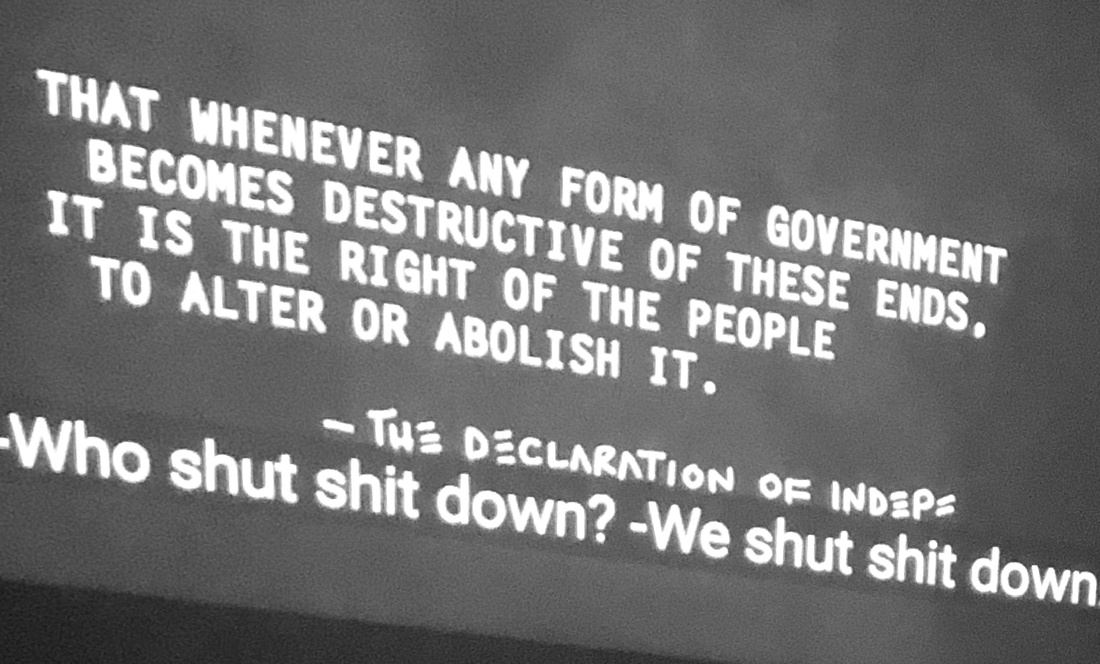

Reports of white Americans flaunting their privilege to protest such meaninglessness started to toll emotionally on me, and many people I know. I turned off the TV and returned back to my silence. This time, though, I seemed to use the silence unconsciously as a meaningful time for reflection. Then, when the temperature began to rise, and video of George Floyd’s brutal murder started to circulate online, a tempestuous storm came through, and through of the quiet backdrop of my quarantine walls, I could hear a rallying cry knocking on the streets. I felt ready. Overnight, the desolation of New York City reversed, and Black Lives Matter organizers brought out thousands upon thousands of protesters fighting against police violence. The weight of the movement, the masses of people all around, and the popularization of the Black Lives Matter messaging makes me curious about whether the silence of quarantine served as a recharge for activists and organizers, a moment of reflective stillness and quiet, in the way it was for me. The first few weeks of protests radiated an energy that was unrecognizable.

In The Temple of my Familiar, Zede, one of the novel’s protagonists, recalls her earliest memories of living a peaceful life. Her small home was always still and quiet, save from occasional rants given by elders, during which she would learn about the white businessmen’s harsh treatment towards the people in her family. Occasionally, too, people would gather and play music, dance or laugh. But the majority of her days were spent appreciating the peaceful silence of her surroundings. It wasn’t until her father fell ill, and white people came into her understanding of the world, that the peace and quiet of her youth faltered. It was the actions of selfish white Americans that broke the silence of the quarantine, the fact of a problem in America caused by whiteness, the reality of police brutality could no longer exist in silence. And the screams of people demanding a stop forced a national reckoning worthy of a rupture in the silence of my days of sheltering in place.

For as much as the protests were reported on the looting, the burning, and the loud anarchical behavior, plus the shooting and tear-gassing by aggressive police officers- that very much was a reality- many days spent protesting were not only peaceful, but quiet. I remember during one particular protest, feeling a sense of quietude sinking in the air and flowing seamlessly through the thousands of bodies present on the street. Many of the protests were marches, that spanned miles of neighborhoods across the city, and it felt like I was in a crowd of a thousand or more people; all quietly contemplating and reflecting as we marched along. Everybody participated with rhapsodic determination, but as I walked along the shutdown roads, crowded with bodies slowly moving along, I noticed a monumental synchronicity of quietude that exists in these incredulous moments of the in-between. In-between deep chants outside the courthouse Downtown, or walking in-between Flatbush and Bedstuy, a great paradox of these protests seems to occur. There are people with no gravity in their shoes, moving with the organizers as they breathe fire of passion for their chanted demands, and the participants in the back repeating with, what feels like, all the fervor in Brooklyn, until the in-between moment trickles in, and brings waves of quiet through the crowds. Perhaps it is the quiet, deep breath the exhausted Black organizers and protesters take for having to muster the same energy that has been required a thousand times over for four hundred years to demand expiation. And maybe too, it was the lethargy of mid-June New York summer heat, but the quiet moments during these protests of such significant monumental weight felt impossible to ignore.

While so many white Americans desperately cling to times of the past, maybe the days when white supremacy was not so often challenged, whether it be through defending the sanctity of statues representing historic racist figures, or pretending everything is okay, in order to return the time before coronavirus plumaged society, or maybe it’s by celebrating spring break to hang on to a sense of nostalgia for the drug-fueled raves of the MTV era, I see the future rolling steadily through our presence. Maybe what we need is not loud buzzers on TV, ringing every time some kid wins a whip-cream licking contest, or white men screaming uncontrollably at a Costco sales clerk patiently asking shoppers to put on a face mask, but instead a prolific moment of quiet. A moment with a quiet that can encounter discomfort, or restlessness, but nonetheless, a quiet that trails on. It would be interesting to see a transformation of the spaces that are traditionally the loudest, the areas occupied by the loudest voices (or, rather the voices that are most often heard, and given allowance to be loud), to “pipe-down” the hegemonic noise, and allow a fulfilling space and time for meaningful quiet. And from the ashes will rise a new, more powerful noise, one of radical change, not of frivolity. Like Robert Browning suggested, the quiet can take on a mind of its own, and whatever it has a mind to do, I think we should begin to allow.